I’ve just bought a Radio Times, although about the only thing I watch on TV is when Liverpool are playing a football match… I’ve bought because there is a picture of Chris Packham on the cover, covered in and surrounded by wild animals and birds. Not because of Chris Packham I might add, but because of the wild animals and birds. He is the guest editor this week, and there are a lot of wildlife/environmental features in it because this week (today in fact) it’s Earth Day. I found myself reading it while I was standing in the Co-op, so I thought I might as well buy a copy. Some of you might know that I’m a big wildlife lover, and if I’m not working, eating, relaxing with my wife or writing, there’s a good chance that I’m either out birdwatching or sorting out photos that I’ve taken while I’ve been out birdwatching.

So why this? I thought today is a good opportunity to flag up our environmental credentials, of which I would say we have three in particular.

1. All our reading rulers and overlays are made of recyclable PET. A lot of non-specialists have jumped onto the visual stress bandwagon now because we have opened up that market over the last 20 years, but they are manufacturing in PVC because it’s cheaper and doesn’t require such high print volumes. Not only is PVC poisonous and stays in the environment for millions of years, but it’s not as clear as PET. So when you buy our coloured overlay products not only are you being kinder to the environment, but you are being kinder to your eyes.

2. All our tinted exercise books (only available in the UK at the moment), as well as all the paper we use in the office and print our own books on (such as Beccie Hawes’s Getting it Right for Dyslexic Learners, in case you didn’t know we published books as well as helped people to read them) are printed on carbon capture paper certified by the Woodland Trust. I’ve even been out planting trees with our paper suppliers.

3. All our exercise books are printed locally, so they have a minimal carbon footprint. By locally I mean about 15 miles away.

So there you go. If you are thinking of topping up – or starting out – on our visual stress products, what better day to do it than Earth Day? Here’s the link: https://www.crossboweducation.com/all-visual-stress

Happy Earthday!

The Big Schools Birdwatch

Free Resources

Children (and adults!) love “spotting” things. I think the game I Spy is written into everyone’s genetic code. What better activity to get them off their devices and outside than the RSPB’s Big Schools Birdwatch, which runs from now until 19th February. This is the link:

https://www.rspb.org.uk/whats-happening/get-ready-for-big-schools-birdwatch

Whatever age group you are teaching, from Early Years to Secondary, free resources are available to help you and your class take part, including differentiated material to support the survey and data analysis. All the resources support curriculum learning and are available bilingually for schools in Wales. RSPB have also got loads of other stuff in their resource library that can help you point your children to the natural world, so check out their website – https://www.rspb.org.uk/

Waxwing Winter

When I’m not sitting at a computer I love to go to wild places with my camera photographing birds. These are waxwings: they aren’t common birds, but occasionally we have what birders call a “waxwing Winter”- this year is one, in fact – when flocks of them, from a handful to hundreds of birds, fly South from their breeding grounds to the warmer climes of the UK and descend on trees that bear berries to devour their fruit. If you see them, it will quite possibly be in a retail park car park or a tree lined avenue on a housing estate. These were two of 18 on a roadside tree in Stoke-on-Trent. Not so wild, then…

A competition

Once I get onto birds I’m capable of going on at considerable length, so I won’t do that. But do check out the Big Schools Birdwatch, and you may also want to point your children to the Big Garden Birdwatch which is also going on now. And finishing on waxwings – there are more of them in the North and East of the country than elsewhere, although that doesn’t mean you won’t find them in the South or West. As well as spotting things, children love a competition. How about “Who can be first to spot a waxwing?” Not many will, because they occur very locally, depending on where the berry-marauding flocks have found a food supply, but it will get them out with their eyes open – especially in tree-lined retail parks. And the great thing about all of this is that you don’t have to be any good at school work, or sports, to succeed. If any of your children spot one, let us know!

Eye Level Reading Rulers – 20 years on (nearly)

It is nearly 20 years since Anne (my wife) and I designed and patented the Eye Level Reading Ruler. At the time, the provision of coloured overlay interventions for visual stress was pretty much the exclusive domain of the optometry profession and the Irlen® Centres. Most schools knew nothing of visual stress and assumed that visual disturbances like reversals and white “rivers” on the page were symptoms of dyslexia. As an SEN teacher myself in the late 1980s (we didn’t call it SEND in those days) I was handed a red coloured overlay “to try with my dyslexic students,” and very quickly dismissed it as snake oil when it didn’t make a difference for the boy I tried it with. Such was my understanding – and that of most of my peers – at the time.

Pushing the Boat Out

That all changed in about 2002 when we looked again at the idea of coloured overlays and thought about how we could employ their benefits in something smaller and more user-friendly than a transparent sheet that covered the whole page. We spoke to the SENCO at a well-known specialist dyslexia school and came up with the idea of dividing a much smaller strip into a narrow edge (for line tracking) and a broad pane (for reading into the paragraph). And so the Eye Level Reading Ruler was born. We met with Prof Arnold Wilkins, head of visual science at Essex university and author of Reading Through Colour (Wiley 2003) to gain a deeper understanding of the science behind the effectiveness of coloured overlays, and eventually pushed the boat out (the boat wasn’t very big in those days) to launch our range of ten colours that covered the full chromaticity of the spectrum, basing our selection on his research.

SEN Product of the Year

At the time, Crossbow Education was known as a supplier of innovative multisensory games, materials and activity books (many of which came out of my own work teaching dyslexic students), but the reading rulers soon became our best-selling product. The visual disturbances (generically called “pattern glare”) often associated with dyslexia are actually caused by visual stress, a separate condition of the visual cortex that is often co-morbid with dyslexia and other SpLDs, and that is brought about by an over-sensitivity to specific wavelengths of light. We began to concentrate our time and resources on developing more visual stress support products, and by the time we had added to the range with A4 coloured overlays, tinted exercise books, our own Visual Stress Assessment Pack, our tinted magnetic marker boards, and more recently our Tint and Track computer app, we were better known for our visual stress support products than the multisensory teaching resources that we started out with. Before long, visual stress was on the radar of most SENCOs thanks to the availability of our inexpensive little reading rulers. Hundreds of schools discovered that they could buy our Visual Stress Assessment Pack for £50.00 to find out for themselves if struggling readers needed an overlay, and more specifically which colour could help, instead of paying more than that, per student, for an outside professional to come in and do the work. In 2014 Crossbow won the prestigious SEN Product of the Year award at the BESA (British Educational Suppliers’ Assn) Educational Resources Awards for our visual stress support resources. Two years later we won the international SEN Supplier of the Year award at the GESS (Gulf Educational Supplies and Services) exhibition in Dubai.

Arguments and problems

Meanwhile, some academics and professionals argued about the efficacy of the use of coloured overlays and reading rulers. Were they just a placebo? Was the design of the research flawed? How valid, scientifically, is the growing body of anecdotal evidence that surrounds the experience of reading through colour? Despite many peer-reviewed studies (including one that used our own products) there were, and still are, many sceptics. And indeed, a genuine problem can be over-reliance on a quick assessment to identify visual stress: improved reading performance with a coloured overlay can occasionally be masking more serious health problems, for example, which is why our literature always recommends that an eyecare professional is also consulted when difficulties with vision are presenting. In addition, the fact that a coloured overlay may improve a child’s reading speed and comprehension doesn’t preclude the possibility of dyslexia (or another difficulty) also having an affect on a child’s performance. Visual Stress often exists alongside dyslexia, but that means that there are two problems to contend with, not just one. Reducing or removing pattern glare with a coloured overlay or reading ruler doesn’t treat the dyslexia: it just makes the words accessible so that the dyslexic child can start learning to decode them.

Is that what you mean by a word?

Fortunately, the positive results of reading through (and, incidentally, writing on) colour seem to have a stronger dynamic than the negatives of the naysayers. I wouldn’t like to say how many times we have had stories of, or from, people young and old telling us how lives have been changed by a simple tinted transparency. These reports may pass under the radar of science, but they are no less true for the people who tell them. We have seen with our own eyes the differences between both the handwriting and the spelling of a child’s work on white paper and on paper of her optimum colour. I have had the privilege of presenting on visual stress at many events in the UK and overseas, and the story that still gives me goose-bumps when I tell it is of the 11 year old boy, a non-reader, whose comment on being given the right coloured overlay to read through after being assessed with our pack (in his case, a double sky blue: he needed a particularly dark tint) was “Is THAT what you mean by a word? Can I start learning to read now?”

The Ripple Effect.

In the last twenty years (nearly) Anne and I have seen our little strips of tinted plastic go round the world, and in that time, especially in the last few years, hundreds of thousands of children (and adults) – maybe more – have benefitted from our design. Not all of these reading rulers have been manufactured and supplied by ourselves, but we take pride in the fact that not only has our contribution made a difference in the world of literacy, but the ripple effect of those who followed where we have led has extended it a lot further.

When we met with Arnold Wilkins all those years ago his passion was that an understanding of the beneficial effects of reading through colour would reach beyond the small group of professionals that were aware of visual stress at the time, and out to the wider reading public. I think we have gone a long way towards helping achieve that. With each new annual intake the journey begins afresh, so we never rest on our laurels, and we have some exciting additions to our range that we will be launching in 2024. So here’s to the next 20 years: watch this space!

Bob Hext November 2023

Heads in the Cloud

We (Crossbow) exhibited at the TESSEN show back in October. It’s by far and away our favourite SEN event, with two full days of seminar programmes and many suppliers like ourselves displaying their wares and talking to teachers, parents, and others with an interest in all things SEND. We have a particularly soft spot for the show since we, basically, launched Crossbow Education there in 1993: just myself, my wife Anne, and five card games that I had developed with the dyslexic students I taught. If there were a long service medal for participation in the show we would probably win it: we have attended every one since 1993 and have seen it go through three separate incarnations. It was a big hole in the calendar when the 2020 show was cancelled due to Covid.

So when October 2021 came along and the show was live again, we were excited to be going back. It was a relatively muted affair though, by contrast to previous shows – the footfall was down by at least 40%, for various Covid-related reasons, and consequently we all felt the draft commercially in terms of reduced orders. Nevertheless, we all agreed as exhibitors that it was “great to be back” and to be actually engaging face-to-face again with the people that we supply and serve, and we accepted the financial hit for the sake of “getting the show on the road” again. It’s an important event in the SEN calendar.

However, my over-riding feelings after the show were of sadness. I wasn’t sad because our sales were down on previous shows, because we weren’t expecting anything else; but I was saddened because of what had happened to the event itself. The TESSEN show – or Special Needs London, as it used to be called, was once a bustling marketplace of publishers and resource suppliers all competing for the attention of the 5,000 or so SEN specialists who were looking for the best materials to meet their widely ranging needs. If you were launching a new SEN product or company it was the place to be. Now it was quiet: not just because of the relative lack of people, but because of the lack of actual “stuff” on display, creating a mix of colours and textures that added to the dynamic “marketplace” feel of the event.

One of my long-standing friends in the industry is the MD of the SEN publishing house Learning Materials Ltd. He wasn’t there this year because he’d had an injury, but it wasn’t just his company that was missing, but actual learning materials – if materials are resources that children and teachers actually get their hands on. Of over 100 companies that were exhibiting at the show in October, only about 15 actually provided tangible resources that supported children with SEND.

What were all the others? Mostly they were online services, online platforms, online programmes, online resources… TESSEN used to be the SEN High Street of Education Town. Now nearly all the shops have shut their doors and either disappeared or gone online, and the marketplace has become a parade of featureless booths and pop-up banners. Of course Covid and schools lockdown has contributed vastly to the proliferation of digital resources now available to schoolchildren. But before Covid things were already going that way, and EdTech has been the Belle of the Ball for a few years now. And my point is this: what has happened to multisensory teaching? Where are VAK – especially K – and multiple intelligences?

When I started teaching dyslexic children in 1988 we were learning that a multisensory approach was the best way of supporting the needs of dyslexic learners, and it soon became apparent that all children benefitted from engaging all their senses in the learning process. Where dyslexia teaching led, mainstream followed. But if the decline in availability of multisensory teaching resources at the TESSEN Show is more than just a Covid-related blip, I would say that it represents a worrying trend. A recent study in Canada examined the associations between screen-time and externalizing behaviour (e.g. inattention and aggression) for 2,427 families of pre-school children. The results of the study indicated that over 95% of the children had access to screen time. For those who participated in screen time for over two hours a day as opposed to less than 30 minutes, it was found that they were seven times more likely to exhibit “externalising” behavioural problems such as inattention, and seven times more likely to meet the criteria for Attention Deficit Disorder (Tamana et al, 2019)

So for the children who struggle most to pay attention in lessons, those with SEND are increasingly fed a diet of activities that increase their inattentiveness. The Belle of the Ball is actually wearing the emperor’s new clothes, and it’s time that educators took their heads out of the cloud.

Do you know what an imposter letter is?

If you are dyslexic you will almost certainly have come across them, without necessarily putting a name to the problem. An imposter letter is a character that is identical with a different one in a font. The commonest imposter is probably a lower case l that is the same as or very similar to a capital I, but there are others, depending on the font. In some fonts l, I, are also easily confused with the number 1 – and when an exclamation mark comes into the picture as well life can get quite complicated !

Imposter letters are among the collection of visual obstacles that a dyslexic reader has to overcome to access text. Pattern glare is another one: text on white backgrounds comprises rows of black stripes, which EEG scans have shown are the very patterns that provoke the most illusions among photosensitive patients. Not everyone with dyslexia experiences the visual disturbances caused by pattern glare; nevertheless visual difficulties often add to the processing problems experienced by people with dyslexia, as well as other SpLDs, particularly autism.

Speed bumps

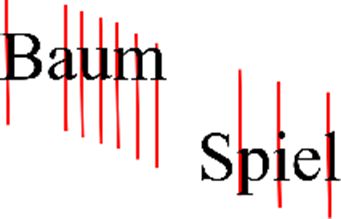

Not only do repeated vertical stripes in a font cause pattern glare; they also appear to actually slow down reading in their own right. Research measuring eye movements showed that the word “Spiel” (three vertical stripes and five letters) took less time to read than “Baum” (7 verticals but only four letters). They are like speed bumps in the reading process. ((Periodic letter strokes within a word affect fixation disparity during reading Stephanie Jainta , Wolfgang Jaschinski and Arnold J. Wilkins )

Which way is right?

Some dyslexic people cannot read directional arrows: they will see a left pointing arrow and want to turn right. Not helpful if you are driving in a one-way system. Left and right arrows mirror each other, as do various letters in many fonts in latinate orthography. B and d are the best known, but p/q are often horizontal mirror letters as well, while n/u often mirror can each other vertically. There are lots of “arrows” to take the dyslexic reader in the wrong direction.

Avoiding the problem

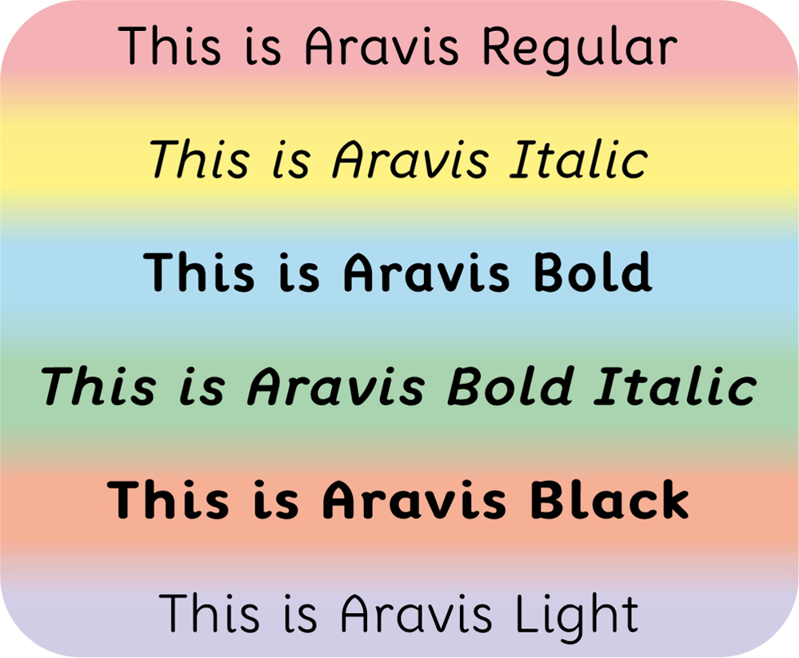

It has been extensively shown that reading through a coloured filter that fits the individual profile of someone experiencing visual difficulties (such as visual stress) can significantly help with the reading process, both improving reading and comprehension. But a lot of these difficulties can be overcome by using a font that is designed to avoid them. And now (ta-da!), after over five years in development, Crossbow have released “Aravis,” the dyslexia-friendly font with no imposter letters, no text mirroring, research-based spacing, and algorithms that are based on the visually relaxing curves found in nature rather than the disturbing repetition of vertical lines common to most standard fonts. Aravis is now the house font at Crossbow Education, so if you are wondering what it looks like , just go over to our website: www.crossboweducation.com. It doesn’t look particularly out of the ordinary, does it – but everything about Aravis is designed to be gentle on the eye, taking the speed bumps and (mis)direction arrows out of reading. We’re still offering it at a promotional price of less than 50%

Still Curing Dyslexia

I’ve just been reading some material online on ‘dyslexia treatments’ that include such diverse “therapies” as inner-ear improvement exercises and electric shock treatment that increases reading speed (http://www.newsweek.com/electric-shocks-help-dyslexic-children-read-faster-442693/) If you do any kind of search on the terms “dyslexia cure” you will find neuroscientific brain training, full-on integrated “systems” that combine everything from diet to brain training, hemispheric stimulation, wobble-boards, music therapy, fish oils, and, I’m sure, plenty more. As anyone familiar with my hobby-horses will know, I am prone to rant about anything that claims that to “cure dyslexia”, even the coloured overlays that we sell shedloads of, so here we go…

Catch-All

We see the words “suffering”, “treatment”, “therapy”, “cure”, and of course “disability”, all associated with dyslexia. Meanwhile Professor Joe Elliott famously states (“The Dyslexia Debate, 2014) that the term dyslexia is “unscientific and should be abandoned”, while at the same time thousands of parents look to that very diagnosis in the hope that it will help provide the support that will somehow shoehorn their child into educational success.

I can see Professor Elliott’s point. Dyslexia has become too much of a catch-all phrase. And if dyslexia can be “cured” by so many diverse treatments, as most often demonstrated by increased reading speed and improved spelling and/or comprehension, is it even the same “condition” that is being treated every time? There is evidence (eg https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/12/161221125517.htm , or https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/06/090624193502.htm) of differences between the brain of a dyslexic person and a neurotypical individual. As the second of those two research articles says, “It is increasingly accepted that dyslexia is not a unique entity, but might reflect different neuro-cognitive pathologies”. One, perhaps, that responds to fish-oils, another one that responds to hemispheric stimulation (whatever that actually is)?

Dyslexic Heroes

I see it like this. Some people’s brains are wired differently from most others, resulting in a combination of strengths and weaknesses that puts them on the edge of any bell-curve distribution that could be labelled “neurotypical”. Those weaker areas will need support if a person is going to succeed in a system that demands strength where they are weak. It seems that there are all sorts of ways of providing that support, some of which I’m sure are more helpful than others. But whatever the different dyslexic phenotypes are, their difficulties in one area are often balanced by great strengths in others, as we know from the Einsteins, Churchills and many other “dyslexic heroes” who have a place in history. The UK disability consultant to Microsoft struggles to read and write, but he finds ways round the problems and provides a lot of support for a lot of people by sharing the solutions he has discovered for himself. If these people had been “cured” of their dyslexia , the world would be a poorer place.

Bottling Fog

There are all sorts of interventions that can help strengthen some of the weaker areas that are often side-effects of the wiring typical of the “dyslexic” brain, and that’s all good. Let’s help where we can, and use whatever works. But at the same time, let’s make sure we look out for and encourage any unusual positives in the person that we are helping, because they could well be supporting us in something where we are weak – because as Shelley Johnston wrote in her excellent blog on this site, “they’re supposed to be like that!” Meanwhile to talk of curing dyslexia is like trying to bottle fog and give it a label, and unfortunately where you see the word “cure”, that bottle usually has a price on it as well, and is reached for in desperation by someone who has been told that there is something wrong with their child.

Thinking and Reading Comfort

Two thought systems

I am in the process of reading “Thinking fast and slow”, by Nobel prize-winning author Daniel Kahnemann. The whole book is a fascinating insight into the workings of the human mind, and how we operate on two distinct levels: system one, which is our instinctive, “autopilot” mode; and system two, which you could call our rational over-ride; the processes of analytical thought which, when we allow it the energy that it needs to function effectively, monitors and controls the instinctive “gut-thinking” promptings of system one. System two needs mental effort; system one operates at an automatic level, feeding our mental circuits instantly with much of the information we need for daily life – “I recognise that face”, “I know that word”, “I understand that sign” etc. There is a lot more to the book, (if you’re interested you can check out the you tube video on https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CjVQJdIrDJ0 ), but what interests me here is how Kahnemann demonstrates a clear connection between reading comfort and thinking levels.

The cockpit

System one is like a cockpit, which maintains and updates current answers to key questions, such as: Is anything new going on? Is there a threat? Are things going well? Should my attention be redirected? Is more effort needed for this task? etc. In assessing this constant stream of inputs, system one is continually deciding whether or not more effort is required from system two. One of the “dials” monitored in this figurative cockpit measures cognitive ease, and its range is between “Easy” and “Strained:’ Easy is a sign that things are going well – no threats, no major news, no need to redirect attention or mobilize effort. Cognitive strain indicates that a problem exists, which will require increased mobilisation of System two.

Many inputs (including the mood you’re in, the familiarity of the task etc) affect this neurological “dial”, but an important one that relates to reading is the clarity of the font. The process of reading familiar words that are clear on the page is a system one activity operating in the “cognitive ease” range, which leaves system two free to work on what the text is about. However if the presentation of the text causes the dial to register cognitive strain, system two is activated to help decipher the font, which suggests that the cognitive resources available for understanding what the words mean are diminished – especially for someone with dyslexia who has multi-tasking difficulties.

Font size

This has important implications in at least two areas. One is the question of font size and font type in children’s text books and examination papers. Research by Wilkins et al shows that typefaces for children become too small too quickly: “Sentences presented in a font of a size larger than is typical for use in material for 5-year olds were comprehended by 7–8-year-olds more rapidly than those of a more conventional size. The difference in size approximated 19% and it resulted in an increase in reading speed of 9%. (Typography for children may be inappropriately designed, Journal of Research in Reading Vol 32 2009, UKLA). This increase in reading speed was statistically highly significant.

On the same issue, I spoke to a lady on the phone just yesterday, who was concerned about her 14 year old daughter’s progress at school. She mentioned in the course of the conversation that her school had reduced their test papers from A4 to A5 page format, with a consequent reduction in font size. Wilkins’s research cited above goes on to recommend 14 pt (this is 14pt) as the optimum size for school texts. Shrinking A4 pages to A5, for the sake of saving paper, will obviously reduce the font size significantly. The implications for cognitive ease are clear. If school testing results are to be a clear reflection of a child’s ability to think, it is critical that font size and clarity are addressed.

Visual Stress

The second issue brings me on to my pet topic, which is visual stress – the experience of discomfort and text distortions that many people experience when reading black text against a white background. Huang et al (2003) suggest that a strong sensorial stimulation – such as a dense written text – might lead to a “reduction in the efficiency of the inhibitory mechanisms in the visual cortex, resulting in an excessive excitation of the cortical neurons, and thus causing illusions and distortions.”* Wilkins and Evans later proposed (2010) that coloured overlays are effective because “they distribute this excessive excitation and thus mitigate the symptoms of visual stress, thus improving written text processing and reading.” In other words, as is now widely accepted and the many thousands of people who use tinted lenses and coloured overlay products would testify, reading against a coloured background tinted to suit an individual’s preference can move the cognitive ease dial from “strained” to “easy”.

And so the two areas of research come together, like an overlay on a page, even, with an inescapable conclusion: if text clarity and font size are indicators of cognitive ease or cognitive strain, what is the effect of visual stress on our ability to think about what we are reading? How often do we read something, and it just doesn’t “sink in”? If this is a result of cognitive strain, we may be experiencing it because we are tired, or preoccupied, or because the ideas are unfamiliar, or because the text is faint or too small – or it may just be that we need to be reading against a different coloured background.

*This principal is known as “cortical hyperexcitability” and is the science behind the coloured overlays, reading rulers and screen tinting software that we supply.

Bob Hext Jan 2018

They Are Supposed To Be Like That!

Why there is no need to “fix” kids with “special needs”.

Guest blog by Shelley Johnston: Dyslexic, doctor, home-schooling mother.

If I am going to have a rant, I will say that I don’t see anyone classifying children as “SEN” because they lack the extraordinary physical energy and courage of my next-door neighbour’s son. In comparison to him, many other children are frankly pathetic. I will say that I don’t see any children being “statemented” because they lack the ability to handle animals the way my childminder’s son can pick up anything from a preying mantis to a chicken and it appears to become tame. Nobody sighs and says “Never mind, dear, we can work on it,” because they can’t write backwards perfectly, as though in a mirror, like my daughter.

But do you know what? When I am old and sick, if I have a heart attack at 3.00 am, I really hope I find someone in A&E who was like my neighbour’s son as a child, because they have the energy to still be firing on all cylinders at three o’clock in the morning.

One day I WILL finally persuade my husband that a large portion of our household income needs to be spent on horses, and if one of those horses gets colic, I’m going to desperately want someone like my childminder’s son to show up and be able to soothe the thrashing hooves and snapping teeth as the poor thing tries to kick and bite its own tummy.

If I need an engineer, I hope they can flip shapes about in their head as easily as my little girl can.

The biggest trouble our children with “special needs” face is our own short-sightedness; our desperation that they go along with the pack, fit the mould and jump through all the hoops – the hoops laid out by the National Curriculum and Ofsted and other well-meaning bodies of people, who don’t seem to understand that Normal Distribution is a bell-curve; that it is NORMAL for people to be abnormal, that whole populations work by having a balance between lots of people who are good at one thing and a few who are good at others.

If we spend all our time trying to narrow the bell-curve and cut off its untidy tails we will find ourselves up the creek without a paddle. We not only do our “special needs” children a grave disservice by teaching them that what they are good at and enjoy is secondary in importance to the things that they are bad at and hate doing, giving them the impression, albeit unintentionally, that they have to pretend to be something else before they are allowed to be themselves. We deprive the rest of the world of their brilliant talents. We bury our mathematicians, our architects, our philosophers, our Chelsea Flower Show gardeners, our Einsteins, our Chopins under a wave of “Yes, dear; that’s nice: you can do it when you have practised your spellings/when you have learned to sit still in class/when you can remember to put your hand up before speaking/ got your marks in your SATS (ooh , don’t get me started!).

Perhaps they aren’t meant to sit still. They can learn to read standing up, lying down, walking around, or sitting up a tree. Perhaps being “good” at school, sticking to all the rules and interacting with 30 children at a time is just exhausting for the child who is so sensitive that they read the signals of a frightened baby animal. And that’s OK: they are meant to be wriggly, or sensitive, or able to write in both directions. It’s our job to give them space to bloom – whether it’s in a mainstream classroom, a smaller group, a quiet place to hide, or not even at school.

But it doesn’t matter what they need: that’s not what this article is about. It’s about how we look at our children, because that is how they look at themselves. Do we feel sorry for monkeys because they can’t swim, or do we let them climb trees?

PS Of course we have to buy a life-boat as well, because we are 21st century parents with a pathological aversion to risk, and even though the monkey lives in a dry jungle we have to cover all our bases, but more on that some other time…

Lifting the lid on “exam factory” thinking.

Lifting the lid on “exam factory” thinking.

In a direct challenge to the government’s performance tables fixation and the use of “exam floor targets” to label failing schools, Amanda Spielman, the head of Ofsted, has said that some school leaders should be “ashamed” of the tactics used to bolster their league table standings. The Ofsted view is that some schools are simply becoming “exam factories”, burdening students with “meaningless exams” to improve their league table results.

Ms Spielman said, “At a time of scarce pupil funding and high workloads, all managers are responsible for making sure teachers’ time is spent on what matters most. This means concentrating on the curriculum and the substance of education, not preparing your pupils to jump through a series of accountability hoops… The idea that children will not, for example, hear or play the great works of classical musicians or learn about the intricacies of ancient civilisations – all because they are busy preparing for a different set of GCSEs – would be a terrible shame.”

The head of the inspectors in England continued, “All children should study a broad and rich curriculum. Curtailing key stage three means prematurely cutting this off for children who may never have an opportunity to study some of these subjects again.

“Rather than just intensifying the focus on data, Ofsted inspections must explore what is behind the data, asking how results have been achieved. Inspections, then, are about looking underneath the bonnet to be sure that a good quality education –one that genuinely meets pupils’ needs – is not being compromised.”

Answer the Question!

Is this the first breeze of a fresh wind about to blow through our Education system? More emphasis on teaching and learning as opposed to just focusing on achievement has got to be positive, and with the current state of uncertainty in the political landscape it is unlikely that the government will do much to oppose the direction Ofsted may be taking. This issue was highlighted in the context of maths learning difficulties at our SpLD Central conference yesterday, where Prof Steve Chinn (author of Maths for Dyslexics, The Trouble with Maths etc) was our keynote speaker. Steve pointed out that a frightening number of 16-19 yr olds were, basically, incompetent at maths. By incompetent I mean that they made fundamental place value errors; couldn’t work our simple fractions etc. By frightening we are talking about over 40%. At or near the top of the pile of achievement-based teaching (ie I want you to give me the answer to this question, now!) is learning times tables by rote. And in February this year we find Nick Gibb telling an education select committee that times tables testing would be returning to primary schools in summer 2019, as the government thinks “Times tables are a very important part of mathematical knowledge.”

Back to Basics

I don’t think any of us would disagree with the value of knowing what, for example, 6 x 7 equals. What Steve was showing us yesterday was the importance of making sure that children know what the numbers actually mean before we ask them to do sophisticated operations with them. In order to achieve that goal we sometimes need to go a long way back into very basic territory, then sometimes further back still, before we can put right errors and misconceptions that have been hard-wired into early learning experiences with number. What is easy to see in the context of maths learning applies right across the curriculum. Insisting on tests for times tables (and don’t forget, schools – we’ll be grading you on how many of your students give the right answers!) is just a symptom of the bigger problem which is driving the education standards it is desperate to improve.

So let’s hope Ofsted have their way, and get to inspect more of what is going on “under the bonnet”. Maybe we should send the schools minister one of our dyscalculia kits…

Writing on the Wall

It’s not often I get excited about government reports, but the article I read in last Monday’s paper has got me blogging. A report by the Commons’ education select committee criticises the focus on technical aspects of reading and writing that was introduced last year by the schools minister, Nick Gibb. The report said: “The committee is concerned by the emphasis on technical aspects of reading and writing and the diminished focus on composition and creativity at primary school. The committee is not convinced this leads directly to improved writing and calls for the government to reconsider this balance.”

The report goes further, in what is a damning account of what it calls the “high stakes” system of Primary assessment (SATS), but it’s the phrase “diminished focus on composition and creativity” that caught my eye.

I used to be an English teacher, and I’ve always loved writing. Right from the very beginning in the Infants, (in the 1950s) and all the way through my school years, different teachers encouraged my ability and gave me the tools to nurture it. I grew to love grammar and punctuation, to understand parts of speech, to recognise the difference between a main clause and a subordinate clause, to know a simile from a metaphor, to correctly punctuate speech, and to generally follow the road map that took me on my journey of creativity. The wonder of being able to enter my imaginary world and walk through it with another person has stayed with me all my life.

What did I need for this journey? I needed words, obviously, and I found them in books I read and stories I was told; and I needed to know what sounds the letters made when I wrote them down. Actually the wheel of phonics that we used then was hardly different from the one that has been re-invented, to the sound of great trumpeting and the ker-ching of much cash, in the last 15 years. And the children it didn’t work for then would probably be the same as the ones it doesn’t work for now. But that’s an aside…

I needed to put words together in sentences, so full stops and commas appeared pretty soon; and then paragraphs and soon the magic semi-colon. I needed these things because they helped me to write, and writing is something I wanted to do: my writing was my world, and it was the place I wanted to visit most of all. In all the beauty and wonder that makes up the brain of a child, isn’t it the imagination, that faculty to compose and create, that we possibly cherish more than anything else and whose passing we lament as the demands of adulthood crowd in? Can anything be more important to a child’s education (from Latin roots Ex out and Duco to lead) than the springboard of his or her creativity?

Of course children need to understand the technical aspects of language, but it must be to the extent to which it serves them in their journey. If we give a child a pair of wheels, a handlebar and saddle, a chain and some brakes, and ask them to learn their various technical attributes, they will soon walk away and look for something better to do. But if put them on a bike and help them to ride, we have started them on a glorious journey that will last for years and go on for many miles. As they get older and more competent we introduce the gears, we show them how to oil the chain, maintain the brakes, raise the saddle, mend a puncture and the rest. And as they take ownership of the bike, the richer the journey becomes.

So it is with language and writing. Mr Gibb and your army of auditors: will you please get on your bikes, and let creativity and composition loose in the classroom again.

Bob Hext is author of the Crossbow publication “How to Write Like a Writer“.